First, whoever says scientists don't have a sense of humor don't have a sense of humor.

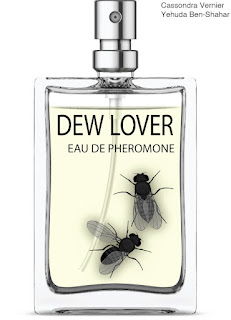

Image credit: This imaginary perfume bottle illustrates the role pheromones play in Drosophila courtship decisions by featuring the silhouettes of a male chasing a courted female. Naming this fictional eau de pheromone “Dew Lover” was inspired by the etymological origin of the genus Drosophila, which is based on the modern scientific Latin adaptation of the Greek words drósos (“dew”) and phílos (“loving”). Vernier et al. show that the coupling of the perception and production of some mating pheromones is regulated by the action of a pleiotropic pheromone receptor. Credit: Digital art by Yehuda Ben-Shahar, Washington University in St. Louis

Now for the main point -- up until recently, much of our understanding of olfactory perception came from looking at receptor activity. You expose a receptor to an odor and see if it lights up, and with that you make a kind of odor map coordinating odorant molecules and receptor proteins.

Things are different now, because instead of just looking at how receptors are stimulated by odors, we also look at how they are inhibited, because it turns out there is just as much to be learned from receptor inhibition as there is activation. And, the interplay of activate-inhibit sure sounds a lot like the ons and offs of computer processing, meaning that the nose-brain may be a lot more useful as a model for a primitive computer than we thought.

Examining the chemicals involved in insect mating

Jan 2023, phys.org

Researchers reported that a single protein called Gr8a is expressed in different organs in male and female flies and appears to play an inhibitory role in mating decision-making. The findings point to one of the ways that flies could put up behavioral barriers to protect against mating with the wrong kind of partner."A single pleiotropic protein can function as both a receptor for pheromones in sensory neurons, as well as contribute to their production in the pheromone-producing cells (oenocytes) of males, by way of a less-understood process."The scientists still have not pinpointed exactly how the chemoreceptor affects the way the signal is produced, but they do know that it causes quantitative and qualitative differences in pheromones. And even small changes in pheromones could be enough to keep closely related flies from finding each other attractive—and change their mate choice behaviors."Based on what we have observed, mutations in a single gene could provide a molecular path for a pheromonal communication system to evolve while still maintaining the functional coupling between a pheromone and its receptor," Ben-Shahar said. "Our research uncovers a potential avenue for pheromonal systems to rapidly evolve when new species arise."

Or when a species decides to rapidly evolve itself; looking at you mass population control.

via Washington University St Louis: Cassondra L. Vernier et al, A pleiotropic chemoreceptor facilitates the production and perception of mating pheromones, iScience (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.105882

Post Script - Pheromones Again

Pachyderm perfume: How African elephants use odor to communicate

Apr 2023, phys.org

We tested the DNA, glands, urine and manure of 113 African elephants in wildlife parks in Malawi to identify family groupings," and "We found a number of chemicals were common to group members, but others that were unique to each individual, and found that smell was used to distinguish characteristics including age, health, reproductive status and family relationships between elephants."We observed elephants greeting each other by squealing and flapping their ears," he said."We believe they're pushing their pheromones towards the other elephant as a sign of recognition."When elephants charge each other flapping their ears, rather than making themselves look bigger, we believe they're blowing their pheromones as a warning not to mess with them.""Some of the animals in the study were bred in captivity, and one of the tricks they'd been taught was to take a tourist's hat and smell it," he said."When the tourist came back hours later the elephant would be able to immediately identify who the hat belonged to."

via University of Queensland: Katharina E. M. von Dürckheim et al, A pachyderm perfume: odour encodes identity and group membership in African elephants, Scientific Reports (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-20920-2

No comments:

Post a Comment